Getting on the same page

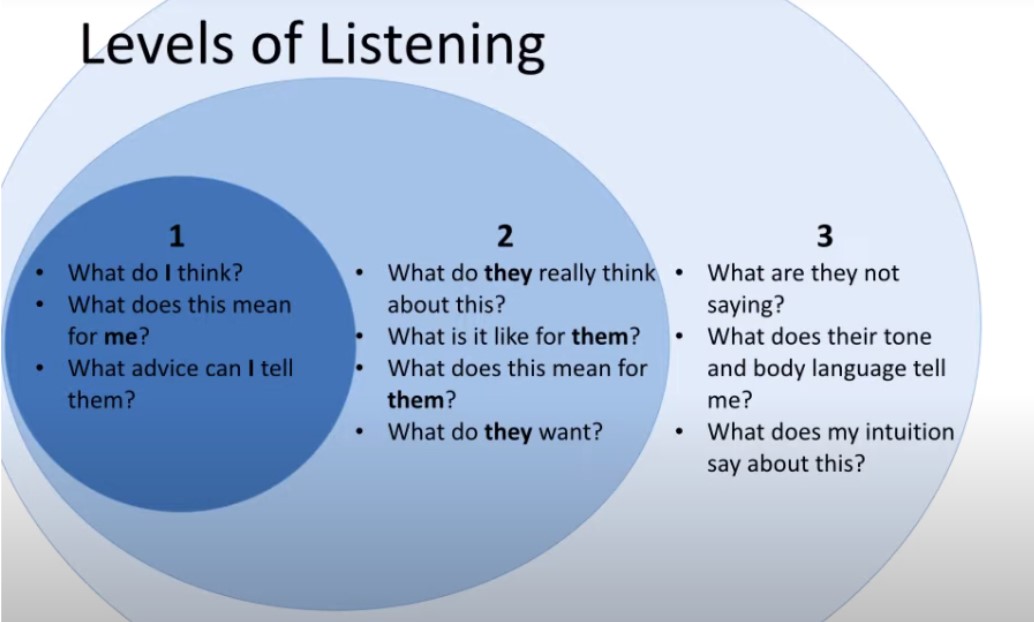

Most disciplines or research group have their own ‘norms’ or ways of working – this is one of the reasons why working across disciplines is so rewarding and exciting. However, it’s important you surface as many of these invisible norms as possible at the start of the project, to help you work well together and minimise misunderstandings later.

Working through the questions below will help you better understand the other disciplines and be clear on expectations. Involve all team members in these discussions and revisit them during the project, in case anything shifts over time.

| Theme | Some questions to explore |

Understanding the other discipline – developing a shared language and understanding of what ‘good’ research looks like: |

|

Understanding each other’s career needs, motivations and expectations: |

|

Anticipated outputs and contributions to these: |

|

How each of us likes to work: |

|

Think in advance about what an author contribution statement would look like for your project outcomes. Check your institutional guidance on authorship and have an open conversation about conventions and expectations. Most projects involve many types of contribution but not all of these meet the criterion of authorship. CRediT (Contributor Roles Taxonomy) is a set of definitions of different types of contribution which might help you put these into words.

These discussions may surface important issues to put into your risk or data management plans, as well as eliciting some core values for how you go about the research, such as embedding inclusivity or researcher wellbeing. You might agree to set joint expectations, e.g. ‘everyone will undertake training in data management’. You could create a team Charter, which acts as a guide for new people and is a living document which evolves over time.

Roles and responsibilities, project and risk management

Your funding bid may already have set out who will do what, but it is important to revisit this as the people come and go or develop new skillsets or other priorities. Have an honest and realistic discussion about other commitments, teaching loads, fluctuating priorities and pressures.

As well as the technical work, who is responsible for overall project management? What does this role include and what do others expect from it?

Looking at your project plan and risks from multiple perspectives

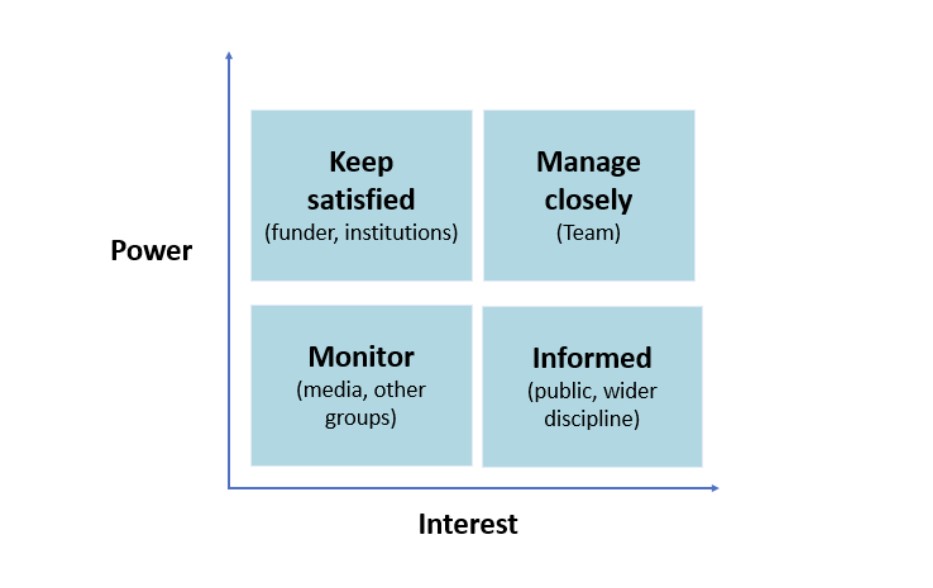

Technicians, research assistants, postdoctoral researchers and students bring insights from the day-to-day practice that more senior people aren’t always aware of so it’s important that representatives from across the team are involved in considering project risks.

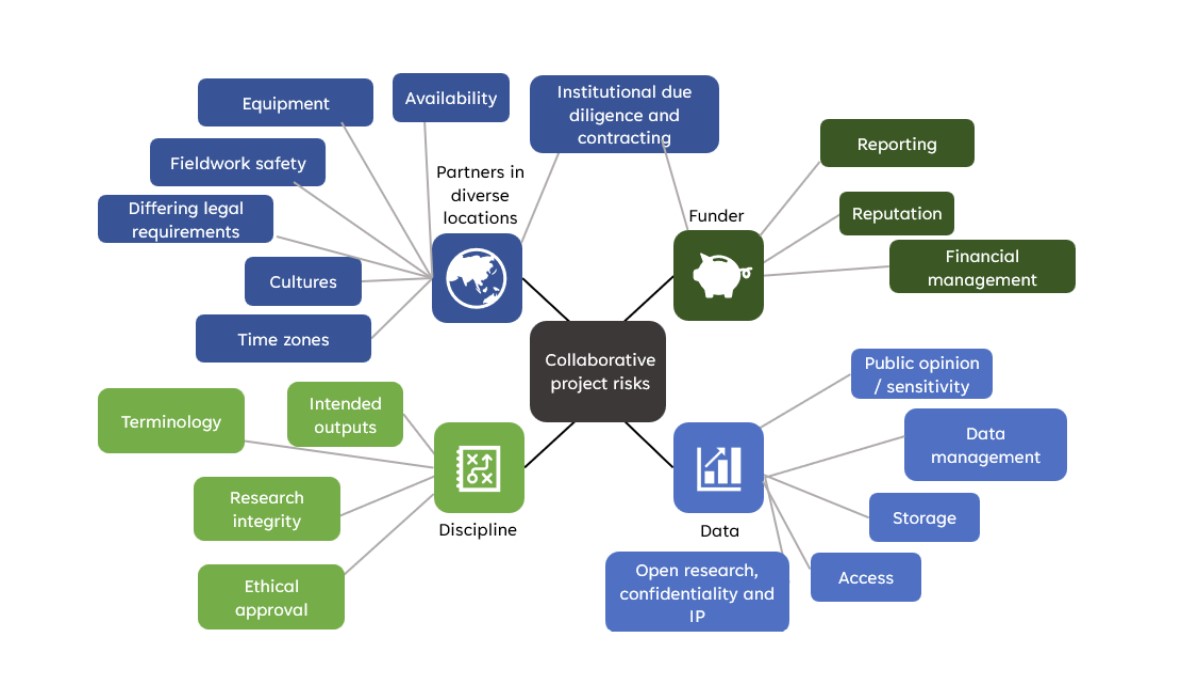

Use the mind map below as a starting point or create your own as a collaboration. Encourage suggestions from across the team on the risks they foresee in the project. This could be things like delays with ethical approval processes or differences in legal requirements on data handling which could slow down getting contracts in place. They could be more about value clashes between partners or a lack of availability / response to key issues. Or you might foresee the issue of scope creep”, where people bring in new ideas which might be exciting but take you further from the original project. Taking each risk in turn, rank them on their likelihood and impact, and put in place a mitigation plan for each, with a nominated person in charge of managing it. Your project board should regularly review your risk register and project dependencies as a standing agenda item in your meetings.

Your institution may offer project management training and templates for risk management to help you think through the requirements of your current project and how to keep things on track.