Access to reliable and timely evidence is essential for parliaments to effectively execute their four main functions of scrutiny, legislation, debating and financial oversight. Sources of evidence can be diverse, with academic research only one type of information that is used in parliamentary processes.

A substantial recent study, led by the Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology (POST), examined the role of academic research in the UK Parliament. Findings revealed that, while research in its broadest sense is useful for parliamentary work, challenges remain, with academic research still “not cutting through”. General surveys and follow-up interviews – including with MPs, MPs’ staff, parliamentary staff and peers – identified lack of accessibility and poor communication as challenges to the use of academic research. For example, evidence in academic sources was commonly thought to be presented in a complicated way, with one MP commenting: “Academic research is usually not that user-friendly from our point of view as users”. An earlier study of UK parliamentary staff also found that academic research was seen to be “too abstruse.”

But what about the challenges for the researchers engaging with decision-makers such as parliaments? Engaging with a select committee is one of the key mechanisms for researchers to present evidence to Parliament. However, the higher education sector (e.g. universities, research groups) is usually underrepresented in written and oral submissions. One 2013-14 study revealed that just 8.1% of oral evidence presented to select committees was from the higher education sector.

Select committees are just one part of Parliament that use evidence; the libraries (eg. the House of Commons Library) and POST also use and gather information. These different parliamentary arenas use evidence in diverging ways, thereby requiring academics to package their research in different ways. Three strategies to enhance engagement as identified by the study of eight UK parliamentary staff are to:

- translate findings more effectively; e.g. creating narrative case studies

- develop relationships with policymakers

- design and conduct research in collaboration with parliamentary actors.

Employing such strategies can mitigate against the current view held by parliamentary staff that academic research is “too abstract from the real world” and “unaware of how Parliament works and what it requires.”

So, it is clear that there are challenges around academic engagement with Parliament. What is less clear is why. What are the barriers to engaging with parliamentary processes? What would motivate academics to engage more with Parliament?

Recently, we launched a nationwide survey to improve our understanding of the policy experience of UK-based researchers. This was part of a project to determine the utility and feasibility of establishing the UK Evidence Information Service (EIS), an innovative model that aims to facilitate research engagement with decision-makers. The EIS would act as a rapid matchmaker to connect research-users (including the parliamentary arenas that use evidence) with the UK academic community in the service of evidence-informed public policy. The EIS project was initially funded by the GW4 Building Communities programme and is now supported by an ERC grant. Partners in the GW4-funded phase included Cardiff University, University of Exeter, PolicyBristol, University of Bath Institute for Policy Research (IPR), UCL and the House of Commons Library.

Although the survey questions were asked in the context of a proposed EIS system, the findings have a wider application to academic policy engagement. The survey was designed by the GW4 academic team with input from the House of Commons Library and the National Assembly for Wales Research Service.

Barriers and motivators for academic engagement with policy

Over 400 research professionals participated in our survey; the findings provide clear guidance on how to improve wider policy engagement with academics.

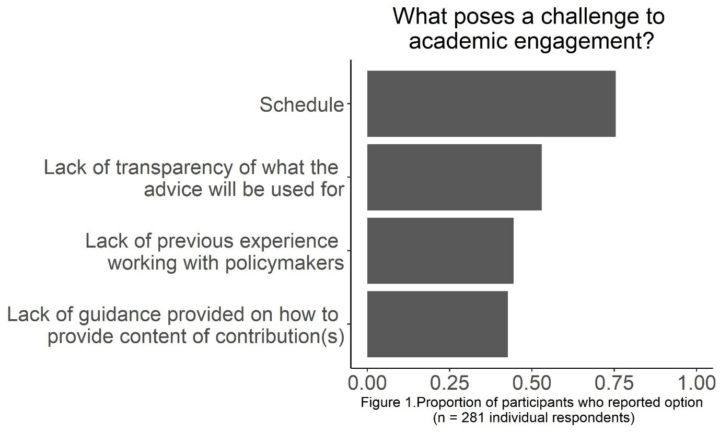

For those researchers who had engaged with the policy sphere previously, interest in policy was a common motivator to provide evidence for policymaking. Despite this motivation, considerable barriers to engaging with processes relating to policymaking were identified; workload of the individual researcher being the most prominent reported barrier. Other barriers identified were lack of transparency about what the research findings would be used for; lack of previous experience working with policymakers; and lack of guidance on content of contributions (see Figure 1).

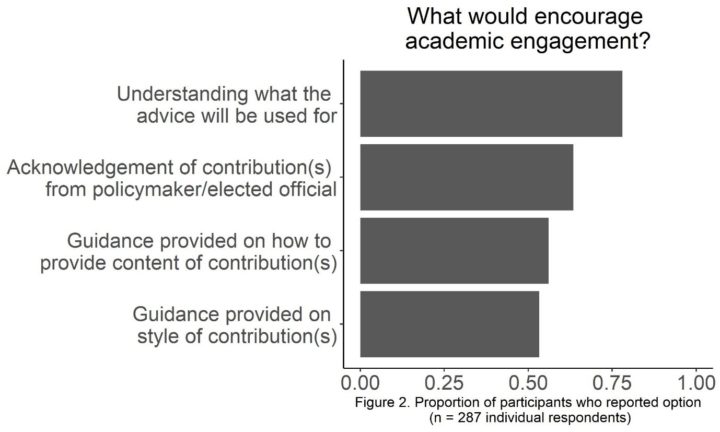

Corresponding with this, academics identified the following as key aspects to encouraging engagement with processes relating to policymaking: understanding what the evidence will be used for, receiving guidance on style and content of contribution, and acknowledgement of the academic contribution by the policymaker or elected official (see Figure 2). Women were significantly more likely than men to select the options relating to guidance.

Future for policy-academic engagement initiatives

These results suggest that any policy-academic engagement initiative needs to:

- provide guidance for academics tailored to the different opportunities to submit research evidence

- be transparent about why and how the submitted research evidence will subsequently be used

- provide clear acknowledgement of the research contribution by academic sources.

The workload of academics still poses a challenge to policy-academic engagement. The recent financial incentive for universities to collect evidence of research impact for submission to the Research Excellent Framework (REF) may facilitate discussions around ensuring researchers have protected time for engagement with decision-makers. For REF2014, 20% of impact case studies outlined engagement with the UK Parliament; if universities want to increase this type of engagement, the major barrier of academic workload will require addressing. For example, funding bodies and universities may consider providing dedicated funds for researchers to provide academic-policy contributions, which are currently lacking.

These survey findings will be used in conjunction with our previous consultation with UK MPs, as well as ongoing discussions with parliamentary staff, to shape the proposed EIS into a working system that benefits all relevant stakeholders. By tailoring the service to overcome some of the barriers to engagement, the EIS can facilitate efficient communication between research-users and research-providers, thus widening the knowledge base of researchers engaging with decision-makers.

Policy-academic engagement is a two-way process with benefits to both sides; by taking into account our findings regarding challenges and benefits for academics to engage, the EIS could enhance the integration of research evidence with policy and practice across the UK.

The EIS team have worked with the House of Commons Library and the National Assembly for Wales Research Service over the last year to trial aspects of the proposed system, and the feedback from this will be assessed in the coming months. Do you have ideas to improve academic-policy engagement, or thoughts on the EIS? We welcome your feedback – please contact Dr Lindsay Walker at walkerl7@cardiff.ac.uk with any comments.

Dr Lindsay Walker is a Research Associate at Cardiff University and an Associate Researcher at the University of Exeter. Lindsay’s key interest is to promote evidence-informed decision-making by facilitating connections between research-providers and research-users. More information about Lindsay’s work can be found on her webpage.

Dr Lindsey Pike is the Coordinator for Social Sciences & Law and Arts at PolicyBristol, University of Bristol. Lindsey is interested in facilitating links between research, policy and practice and tweets at @lindsey_pike.

Marsha Wood is a researcher at the Institute for Policy Research (IPR) at the University of Bath. Marsha works on a variety of research projects and project development of relevance to policy debate and decision making. More information Marsha’s work can be found here.

Dr Hannah Durrant is the research lead at the Institute for Policy Research (IPR) at the University of Bath. Hannah delivers the IPR’s research strategy with a focus on establishing and building relationships between IPR’s research and the policy world. More information about Hannah’s work can be found here.

This article has been reposted from the LSE Impact Blog with the permission of the authors.