With Brussels and London having radically different attitudes to regional policy, Professor Kevin Morgan looks at what lies ahead for UK regional policy post Brexit. The original version of this article can be found at Cardiff University’s Welsh Brexit blog.

Regional policy was invented in Britain

The first country to industrialise, Britain was also the first to de-industrialise when its heavy industries – coal, steel, shipbuilding and the like – collapsed in the inter-war depression.

Although it was too little too late, the Special Areas Act of 1934 saw the birth of the world’s first regional policy, which was designed to mitigate the socio-economic crisis of the depressed areas – the areas where the heavy industries were all clustered.

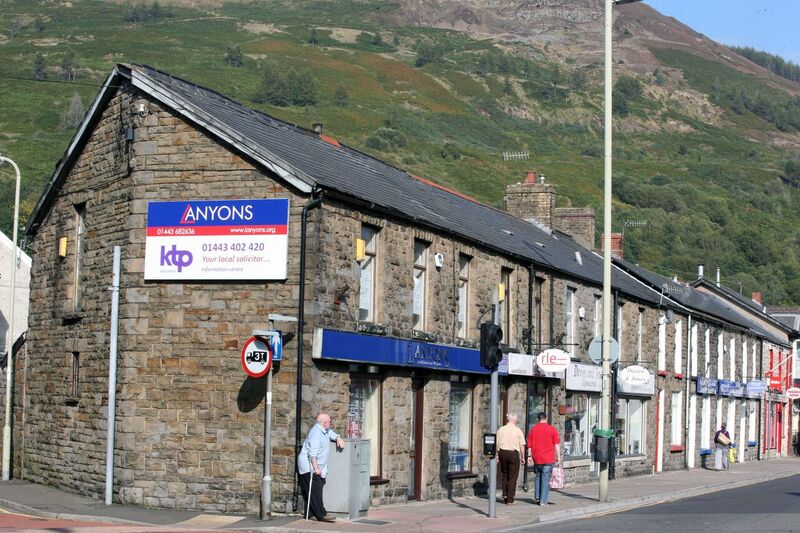

Of the four depressed areas designated for relief in the 1930s – South Wales, North East England, West Cumberland and Clydeside – only South Wales retains the poorest status today, signalling a deep developmental failure and a devastating indictment of more than 80 years of British regional policy. In the current round of EU regional policy (2014-2020) West Wales and the Valleys is a “less developed region” in the regional classification system.

The rise and fall of British regional policy

Since its birth in the 1930s, regional policy has gone through two major phases – the rise and fall of British regional policy, followed by the advent of EU regional policy.

There are valuable lessons to be learned from both phases when we think about how to re-invent regional policy for Post-Brexit Britain.

The “golden age” of British regional policy (late 30s to mid 70s) was predicated on a donor-recipient model of regional development. The “donor regions” were the over-heating regions of South East England and the West Midlands, where industrial development certificates controlled growth (the stick) and financial incentives (the carrot) combined to persuade firms to locate their factory extensions (branch-plants) in the former Special Areas to the north and the west.

This donor-recipient model imploded when formerly prosperous regions like the West Midlands fell on hard times following the travails of the car industry.

If post-war regional policy was undermined by economic decline, the post-war political settlement on which it was predicated was overthrown by Thatcherism, which changed the rules of the territorial game because regional policy shifted away from redistributing investment between regions to promoting growth within regions, a form of regional autarky that exists to this day.

The rise and fall of EU regional policy

Britain was also involved in the invention of the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) in 1975, created to satisfy UK concerns about the agricultural bias of the budget.

But European regional policy really came of age in 1988, when the European Commission (EC) introduced four key principles for regional intervention, namely:

- concentration – to focus resources on key objectives

- multi-annual programmes – to introduce longer term planning

- partnership – to involve regional and local authorities

- additionality – to make sure EU money was additional to (and not a substitute for) member state money

Since EU regional policy came of age in 1988, there have been five multi-annual programmes, the current one running from 2014-2020.

And although each programme had its own nuances, four trends stand out.

First, the most dramatic trend since 1988 has been the growing significance of the innovation priority. From just 4% of the 1988-93 programme, innovation-related measures have grown rapidly, accounting for 45% of the current programme. This shift has been a big challenge for less developed regions because they don’t have the regional ecosystems (composed of universities and firms) to absorb innovation funds as easily as they could absorb funds for new roads and the like. Regional innovation policy may help to nurture the knowledge economy in the long term, but what does it do for jobs and wellbeing in the short term?

Second, another key trend has been the growing emphasis on results. Until the current programme the European Commission was largely concerned with what it called “absorptive capacity” – the regional authorities’ ability to spend funds in a regulatory compliant manner. Now there is a belated emphasis on results, stressing the outcomes of the policy rather than the policy process itself. To be effective, however, a results-based regional policy needs better indicators, stronger and more credible conditionalities and a monitoring and evaluation system that gives parity of esteem to creativity and compliance. Although EU regional policy aims to promote experimentation and learning, these critically important attributes are in fact smothered by a compliance culture that favours conformity over creativity.

Third, the emphasis on results has triggered a debate about the goals of regional policy. Time was when regional policy was purely concerned to reduce unemployment and facilitate industrial reconversion. But, since the economic crisis in 2008, the European Commission concedes that regional policy needs to address a wider set of disparities – particularly in environmental quality, social wellbeing and governance capacity – goals embodied in the current commitment to “smart, sustainable and inclusive” growth.

And fourth and finally, the regional development debate has undergone a marked institutional turn in recent years in response to burgeoning evidence that the quality of government and the calibre of public sector institutions play a major role in fostering/frustrating development.

All these issues – balancing the goals of innovation and wellbeing, emphasising policy outcomes and holding institutions to account for their performance – will need to be addressed by a revamped British regional policy when the reign of EU regional policy ends in 2020.

Post-Brexit Britain: Threats and Opportunities

From a regional policy perspective, Brexit raises an issue that dwarfs all others and it is this: will London provide the same level of support after 2020 that is currently on offer from Brussels? All the assisted areas in the UK need to concert their efforts to demand a regional policy that is at least as generous as current levels of support.

What worries people in the poorer areas of the UK is that Brussels and London have radically different attitudes to regional policy – a commitment to “cohesion policy” is inscribed in the DNA of Brussels, but Conservative governments are more inclined to balance the budget and shrink the state through “a third parliament of austerity” as the Institute for Fiscal Studies put it recently.

If austerity remains embedded in the DNA of the next Conservative government, as seems likely, the biggest threat is to those areas that currently enjoy the highest level of European regional aid – namely Wales and South West England, where the less developed regions of West Wales and the Valleys and Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly are located.

The future need not be all doom and gloom. Brexit offers a real opportunity to re-invent British regional policy by building on the best features of EU policy while avoiding the worst features – and the latter would include the excessively prescriptive priorities, the rigid distinction between different types of region and an audit culture that kills creativity in the name of compliance.

Kevin Morgan is Professor of Governance and Development in the School of Geography and Planning at Cardiff University, where he is also the Dean of Engagement. He is currently a member of the European Commission’s Mirror Group of special advisers on Smart Specialisation.