GW4 held a Climate Resilience workshop in early May for researchers to discuss the potential to collaborate as GW4 to deliver the step change necessary within this broad research area. Here, Dr Freya Garry, Postdoctoral Research Associate at the University of Exeter explains what’s in a name.

As an early career climate researcher, new to the growing field of science around resilience, I attended the GW4 workshop and was struck by the long discussions around what resilience means. Dame Julia Slingo, Former Chief Scientist of the Met Office, facilitated some of these discussions, commenting that working at the interface of different research disciplines is always very challenging but that it is encouraging to see researchers coalesce around a topic.

However challenging, it is very important to define how we understand the term ‘resilience’ before trying to construct a research project. Starting at the workshop I started to collate different definitions from attendees, and realised that there are a whole variety of things talked about under this umbrella term.

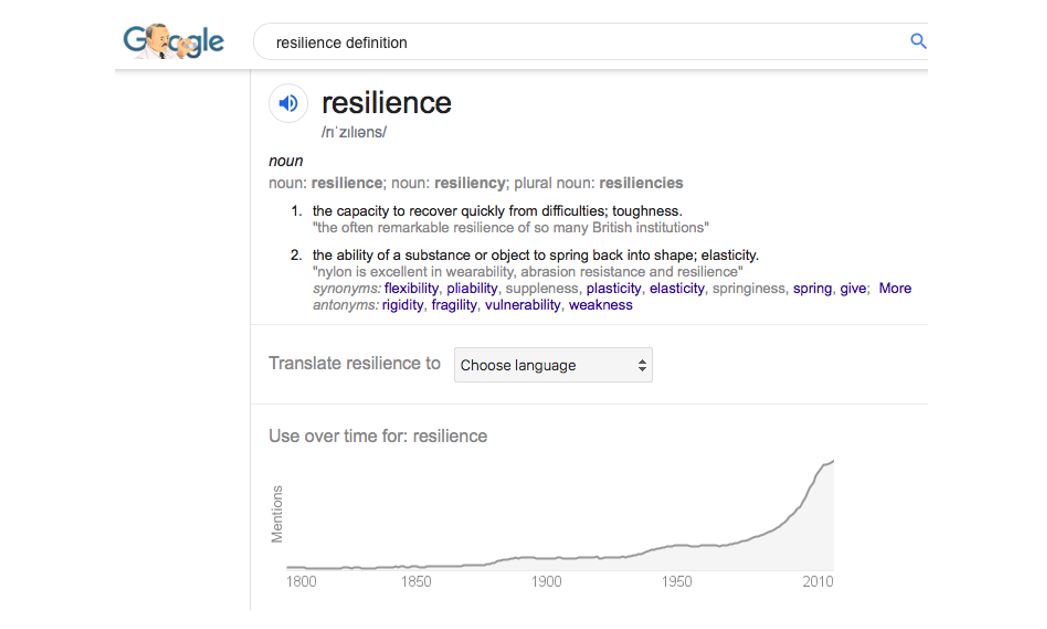

Google provides general definitions around resilience and also highlights the extraordinary growth of this term over recent decades (see image above). Personal resilience is an important part of our daily lives and mental wellbeing, but when we talk about the climate or natural environment, what does it mean to ‘recover’ or be ‘flexible’?

From a numerical perspective (those from a mathematical background), suggestions included:

The ability of a system to resist change following a perturbation and if subjected to change to revert back to its initial state.

A dynamical process at equilibrium is resilient on a timescale T if there are typical perturbations over timescale T and natural system dynamics bring it back to the same equilibrium.

These definitions are useful for building models of earth system behaviour, and statistical techniques can be used to identify changing resilience in the natural world. However, not every perturbation is significant, and there may be ‘special cases’ where you don’t require a system to revert to its initial state following a certain perturbation. A system may not need to be resilient in every way.

The workshop also provided the opportunity to hear from external funders, such as NERC, ESRC and Wellcome Trust regarding climate related funding calls. We heard how the Wellcome Trust are aiming to achieve:

A world in which the natural systems that support health are sustainable across generations, enabling health for all people

For me, this concept of ‘sustainable across generations’ is key. When we talk about climate resilience we are usually talking about the world that our children and grandchildren will inherit, not about long geological timescales.

Others suggest that we should not actually focus on resilience at all in terms of the strength, flexibility or sustainability, of a system but instead we should be concerned with vulnerabilities, risks and adaptation. Returning the climate or ecosystem to a set point in time is of course not likely to be achievable, and often we make choices to embrace certain changes and choose what we protect (some examples: managed flood retreat, moving populations, accepting certain damage or a lower level of service). Resilience is sometimes used as a catch all term for talking about mitigation and adaptation associated with climate change, and the technological and societal changes that we need to make to preserve humanity’s future and the natural environment that we grew up in.

Resilience is now a truly multi-disciplinary term, blending the mathematical and scientific definitions with social concepts such as power and autonomy. We know that climate change is disproportionately affecting the poorest and most vulnerable countries. It is key to consider: whose resilience are you talking about?

From a social perspective, there was further scepticism regarding the usage of the word resilience:

True resilience can only be developed following breakdown and collapse of the old systems to create sustainable transformative change.

Perhaps a resilient planet can only be achieved with radical changes; the current system may be too unsustainable to ever be resilient in the mathematical sense, and we cannot achieve resilience without substantive systems change. It may be that humanity needs to re-evaluate whether some of the ‘positives’ we currently assess society by (e.g. linear growth and large GDP) are compatible with achieving climate and ecological resilience in the twenty-first century.

Resilience can be used to describe characteristics of some negative societal behaviours: inequality and poverty are both very resilient. When we talk about resilience, maybe we don’t want to assume that we want to stay in the same state (as we assume when we model a system). Instead, perhaps our goal should be to move to a future flexible state that satisfies our social and ecological values.

When we use climate resilience as a call to action, we may find that resilience as a term is too passive and that it doesn’t convey the urgency that climate scientists and activists want to communicate: that transformative action is required now, that we need radical changes that take us off the ‘business as usual’ path to a sustainable future.

I have covered just a few perspectives of the word resilience here, captured over just one day workshop and through my perspective as a climate researcher. There will be many usages or ideas associated with the term resilience that I have not touched on. However, what is clear, is that whether you are a scientist, a policymaker or an activist, to use the term resilience with any meaning, you need to clarify who you are trying to engage with, what that term means to them, and what problem are you trying to address?

Thanks to all participants of the GW4 Climate Resilience Meeting on 9 May 2019, with special thanks to Dr Kirsten Lees and Joshua Buxton (Global Systems Institute, University of Exeter) for their comments.